By Glynnis MacNicol, NY Times

“It’s a radical act to publish women’s writing, and an equally radical act to keep it in print.”

— Gloria Steinem

It’s 1969. Across America, the culture wars are raging.

At Goucher College, a private liberal arts school outside Baltimore, students enrolled in an 18th-century literature class take one glance at the syllabus and promptly ask their professor: “Where are the women authors?” The professor, herself a woman, is stumped. “There are none, because I’ve not read any,” she tells them.

The stumped professor was Florence Howe, who died in September at 91, and this story, as she often explained, is how her lifelong project, the Feminist Press — now in its 50th year — was born.

Initially, Ms. Howe proposed a series of short books to be written by famous contemporary women about women of the past. She approached three separate academic presses. But when they turned her down, she went wider, even taking her idea to Bob Silvers, the founding editor of The New York Review of Books. While the people she spoke with were excited by the idea, the financial managers were decidedly not; there was, she was told, “no money in it.”

According to her lengthy 2011 autobiography, “A Life in Motion,” Ms. Howe wasted no time on disappointment, instead pivoting to publish the series herself with her husband’s help. She credits her husband with the concept as well as the name, the Feminist Press. “I could call it the Feminist Press, since he would be a part of it, and feminist was a non-gendered word that included men,” she wrote.

Florence Howe, center, with staff members of the Feminist Press in 1972. Robert M. Klein

News of the Press spread quickly. “Word traveled very fast even though we had no fax, no email, no computers,” Ms. Howe recounted in an interview to mark her 90th birthday. I said, “If at least 25 people show up” to my house in Maryland, “and they agree to meet at least twice a month, we’ll have a feminist press.”

Fifty people showed up.

The Press’s original mandate was to unearth forgotten female writers for the purpose of academic study. “What I wanted were books that could be used in the classroom,” Ms. Howe said in an interview last summer for this story, conducted with the help of Jisu Kim, a senior staffer at the Feminist Press. “Always, that was my goal.”

Many “really important books” had gone out of print simply because they were written by women, says Jennifer Baumgardner, executive director and publisher of the press from 2013 to 2017.

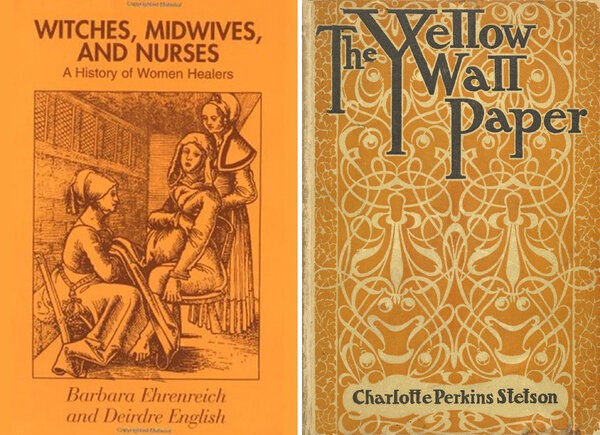

First up was Rebecca Harding Davis’s novella “Life in the Iron Mills,” originally published anonymously in The Atlantic Monthly in 1861. Next, “The Yellow Wallpaper,” by Charlotte Perkins Stetson (also: Charolotte Perkins Gilman), a title that languished in obscurity after its publication in The New England Magazine in 1892, but is now recognizable to nearly everyone who’s taken a women’s studies course.

“Without the Feminist Press, we might not have known that women have always been writing our hearts out,” Gloria Steinem says. “We would have gone on thinking we were inventing the wheel instead of understanding that our mothers and grandmothers had been speeding along on their own. And we definitely wouldn’t have been able to read our counterparts in Africa or Asia.”

“The Yellow Wallpaper” and “Witches, Midwives, and Nurses” were early, important books for the Feminist Press.

Soon, then-present-day writers were added to the mix. In 1972, Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English brought their wildly successful self-published pamphlet, “Witches, Midwives & Nurses” to Ms. Howe.

“We didn’t even think of going to a commercial publisher,” says Ms. Ehrenreich, the writer and political activist, who later penned the international best seller “Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting by in America.” “We wanted to feel very free in what we said.” The Press “was part of our movement as feminists.” More than four decades on, “Witches, Midwives & Nurses” remains the publisher’s strongest seller, a must-read in the midwife community.

The press also helped sweep along the rising Second Wave feminist movement. Writers for Ms. Magazine were sent to the Press to publish their long-form work, according to Ms. Steinem.

In the subsequent decades, the relevance of the Press followed a similar trajectory to the women’s movement: vibrant and essential at times, then slowly receding from view as the culture turned its attention elsewhere, until the next generation of women emerged with a fresh and urgent mandate to point it in a new direction.

Ms. Baumgardner, for instance, describes thinking of the Press as a “very emotionally significant relic” when she first encountered it in the early ’90s, “as opposed to something that I set my watch by.”

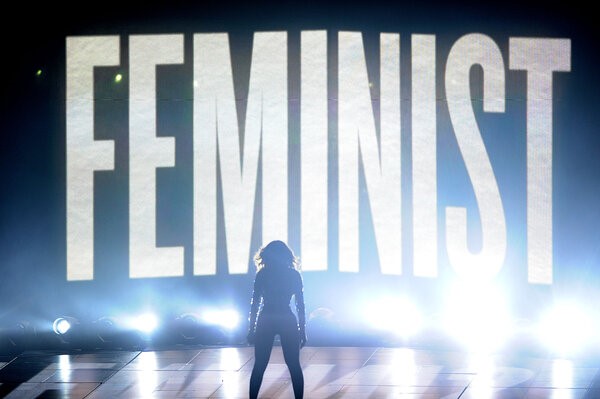

Beyoncé performed onstage at the 2014 MTV Video Music Awards.Jason LaVeris/FilmMagic, via Getty Images

But it changed once again in 2014 when Beyoncé flashed the word FEMINIST behind her at the 2014 MTV Video Music Awards. Then followed the election of Donald J. Trump and the global resurgence of the #MeToo movement, which thrust feminism back into the mainstream, along with the Press.

“Everybody who had been, ‘Well, at least we don’t use the word “feminist,”’ had to scramble to catch up,” notes Ms. Baumgardner, who emphasized the Feminist Press had long been intersectional in its approach. “It already had all this authority in that space.”

Jamia Wilson, who at 37 was named executive director and publisher in 2017 — both the youngest person to ever hold the position and the first Black woman — sees similarities between the era when the Press was founded and the current one, where, she says, “It’s extremely important for us to be an unapologetic feminist voice, no matter what happens.”

“When ‘feminist’ was hashtag trending,” stresses Ms. Wilson, “we thought, ‘Great, but we were feminists before this happened.’ And we will continue to carry this mantle. We want everyone to be able to recognize themselves in a book.”

Today, the Press employs five full-time staff members, three of whom are editors, and publishes between 15 and 20 titles a year. The offices (when people are able to get back to them) are at the CUNY building on Fifth Avenue in New York City, across the street from the Empire State Building, and above the former location of B. Altman, best known to current generations as the workplace of Mrs. Maisel. In normal years, it also hosts the annual Feminist Power Awards to honor female visionaries in a variety of fields.

Unlike many larger publishers, the Press is entirely mission driven, Ms. Wilson says, and this informs everything it does. “Your advance might not have as many zeros as other places,” she says, “but your author care will be unmatched.” She compares the editing process to “going to the gynecologist and they put warm mitts on before they examine you — someone thought about your dignity.”

Ms. Wilson also notes that, thanks largely to the political climate, she increasingly “gets the sense that authors like to be associated with the Feminist Press as part of the positioning of their book.”

Dr. Brittney Cooper, who co-edited the The Crunk Feminist Collection, comprising essays on intersectionality, feminism, politics and culture based on the popular blog, says she is thankful the Feminist Press chose to publish the collection “without a lot of rigmarole.” It “represented an investment, and making sure that much of the thinking happening in the digital feminist era would be sustained for generations to come.”

While the combination of the coronavirus pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests rocked much of the publishing world — independent bookstores, especially, are struggling and the largely white publishing industry has been undergoing a monthslong reckoning — the Press has remained steady. Ms. Wilson credits its long history in “gender justice” spaces, as well as 50 years of dealing with the financial challenges of the nonprofit space.

“It’s not the first time we’ve seen adversity and had to work together to transform,” Ms. Wilson says.

At the end of September it was announced that Ms. Wilson would be leaving the Press to take over as executive editor at Random House. She says since the announcement the board has been inundated with applications for the role. “I’m excited to see people’s excitement about this opportunity,” Ms. Wilson says. “The minute that we announced, people were like, ‘So how can I apply for that?’”

“Feminist institutions are the things left standing after protest goes away,” Dr. Cooper says, “and that longevity gives us an anchor point for each new generation of activists that arises.”

Indeed, “It’s a radical act to publish women’s writing,” Ms. Steinem says, “and an equally radical act to keep it in print.”